Please see the end of the article for a summary of the main points or jump ahead to verses 4.31 and 4.32 for the part where the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad equates Deep Sleep with Brahman.

Also see:

Deep Sleep and Self-Realisation

Ramana Maharshi: the method of wakeful sleep (Jagrat Sushupti) to attain liberation

(I’ve just typed this up quite quickly so, as usual, apologies for any spelling or grammatical mistakes)

The teaching of the three states (ie. the waking, dream and deep sleep states) is a staple Vedanta teaching and often the source for this teaching is cited as being the Mandukya Upanishad. However, the three states are presented and analysed in the earlier-written Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, especially in section 4.3.

Dry Upanishadic Humour

Section 3 of the Brihadarankaya Upanishad consists of a conversation between King Janaka and the Sage Yajnavalkya. Now for those of you who have not encountered Sage Yajnavalkya, he is quite a character at times, demonstrating the dry humour present in many of the Upanishads. Here is an example from Section 3.1 of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad:

3.1.1: Om. Janaka, Emperor of Videha, performed a sacrifice in which gifts were freely distributed among the priests. Brahmin scholars from the countries of Kuru and Panchala were assembled there. Emperor Tanaka of Videha wished to know which of these brahmins was the most erudite Vedic scholar. So he confined a thousand cows in a pen and fastened on the horns of each ten padas of gold.

3.1.2: He said to them: “Venerable brahmins, let him among you who is the best Vedic scholar drive these cows home.” None of the brahmins dared. Then Yajnavalkya said to one of his pupils: “Dear Samsrava, drive these cows home.” He drove them away. The brahmins were furious and said: “How does he dare to call himself the best Vedic scholar among us?” Now among them there was Asvala, the hotri priest of Emperor Janaka of Videha. He asked Yajnavalkya: “Are you indeed the best Vedic scholar among us, O Yajnavalkya?” He replied: “I bow to the best Vedic scholar, but I just wish to have these cows.” Thereupon the Hotri Asvala determined to question him.

Here we have a scenario in which King Janaka effectively sets up a challenge to see who the best Vedic Scholar is, with the prize being one thousand cows. However before the challenge has even begun, Sage Yajnavalkya simply asks one of his students to take the cows. When challenged by the other scholars to see if he is really the most knowledgeable in the Vedas, Yajnavalkya dryly replies that irrespective of who the best scholar is, he just wants the cows! For me this demonstrates the humour, irony and rebellious spirit that is present throughout many of the Upanishads, but this humourous aspect of the teaching is often missed when the approach becomes overly intellectual and analytical.

The Guru wants to get paid!

Anyway, back to the three states and section 4 of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. In section 4.3 Yajnavalkya goes to King Janaka with the intent of not speaking, but because he had previously made a promise to King Janaka that he will answer any questions King Janaka asks, we obtain the dialogue of section 4.3 which pertains to the three states. In Shankara’s commentary on these verses he explains that the real reason Yajnavalkya visits King Janaka is to gain more wealth and cattle from the King, and throughout the following dialogue King Janaka keeps on gifting increasing numbers of cattle to Sage Yajnavalkya.

4.3.1 Yajnavalkya called on Janaka, Emperor of Videha. He said to himself: “I will not say anything.” But once upon a time Janaka, Emperor of Videha and Yajnavalkya had had a talk about the Agnihotra sacrifice and Yajnavalkya had offered him a boon. Janaka had chosen the right to ask him any questions he wished and Yajnavalkya had granted him the boon. So it was the Emperor who first questioned him.

Shankara’s commentary on the above verse reads as follows:

‘Yajnavalkya went to Janaka, Emperor of Videha. While going, he thought he would not say anything to the Emperor. The object of the visit was to get more wealth and maintain that already possessed….’

Note how this is contrary to how many nowadays state that a true teacher would not accept money or material objects for their teaching. In this, the oldest, longest and perhaps the most authoritative of Upanishads, we have the reverse situation! Again, such is the often dry humour of the Upanishads!

No immediate answers…

In the next verses, verses 4.3.2 to 4.3.6 Yajnavalkya reveals that the Self is the Ultimate Reality upon which all stands. You can see that Yajnavalkya does not give the ultimate answer straight away, but only when pressed by King Janaka does he eventually reveal the Self as the true answer he is looking for. My reading of this is that Sage Yajnavalkya only wants to give the teaching to those who are truly intererested, who are truly enquiring, and not to those who merely accept the first answer given to them:

4.3.2. “Yajnavalkya, what serves as light for a man?” “The light of the sun, O Emperor,” said Yajnavalkya, “for with the sun as light he sits, goes out, works and returns.” “Just so, Yajnavalkya.”

4.3.3. “When the sun has set, Yajnavalkya, what serves as light for a man?” “The moon serves as his light, for with the moon as light he sits, goes out, works and returns.” “Just so, Yajnavalkya.”

4.3.4. “When the sun has set and the moon has set, Yajnavalkya, what serves as light for a man?” “Fire serves as his light, for with fire as light he sits, goes out, works and returns.” “Just so, Yajnavalkya.”

4.3.5. “When the sun has set, Yajnavalkya and the moon has set and the fire has gone out, what serves as light for a man?” “Speech (sound) serves as his light, for with speech as light he sits, goes out, works and returns. Therefore, Your Majesty, when one cannot see even one’s own hand, yet when a sound is uttered, one can go there.” “Just so, Yajnavalkya.”

4.3.6. “When the sun has set, Yajnavalkya and the moon has set and the fire has gone out and speech has stopped, what serves as light for a man?” “The self, indeed, is his light, for with the self as light he sits, goes out, works and returns.”

4.3.7 “What is this Self”….

The three states…

…waking and dream

In the next few verses Yajnavalkya teachings that the Self floats between two states, the dream state and waking state, but remains unaffected by theses states, returning to the state of deep sleep when not in dream or waking. All this time Yajnavalkya receives more and more cattle from King Janaka for his teachings! Here is a description of the dream state by Yajnavalkya, in which he explains the dream is a mere unreal projection:

4.3.9 and 4.3.10 ….”And when he dreams, he takes away a little of the impressions of this all-embracing world (the waking state), himself makes the body unconscious and creates a dream body in its place, revealing his own brightness by his own light-and he dreams. In this state the person becomes self-illumined. There are no real chariots in that state, nor animals to be yoked to them, nor roads there, but he creates the chariots, animals and roads. There are no pleasures in that state, no joys, no rejoicings, but he creates the pleasures, joys and rejoicings. There are no pools in that state, no reservoirs, no rivers, but he creates the pools, reservoirs and rivers. He indeed is the agent.

Similarly in verse 13:

4.3.13. ‘In the dream world, the luminous one attains higher and lower states and creates many forms – now, as it were, enjoying himself in the company of women, now laughing, now even beholding frightful sights.

Next Yajnavalkya describes how the Self, referred here by the term Purusha, which literally means ‘supreme being’ or ‘supreme person’ (think ‘higher-self’), floats between two states, the dream state and waking state, but remains unaffected by theses states, returning to the state of deep sleep when not in dream or waking. He receives cattle for his teachings here:

15. Yajnavalkya said: “The entity (purusha), after enjoying himself and raoming in the dream state and merely witnessing the results of good and evil, remains in a state of profound sleep and then hastens back in the reverse way to his former condition, the dream state. He remains unaffected by whatever he sees in that dream state, for this infinite being is unattached.” Janaka said: “Just so, Yajnavalkya. I give you, Sir, a thousand cows. Please instruct me further about Liberation itself.

16. “Yajnavalkya said: “That entity (purusha), after enjoying himself and roaming in the dream state and merely witnessing the results of good and evil, hastens back in the reverse way to his former condition, the waking state. He remains unaffected by whatever he sees in that state, for this infinite being is unattached.” Janaka said: “Just so, Yajnavalkya. I give you, Sir, a thousand cows. Please instruct me further about Liberation itself.”

…and deep sleep

17. Yajnavalkya said: “That entity (purusha), after enjoying himself and roaming in the waking state and merely witnessing the results of good and evil, hastens back in the reverse way to its former condition, the dream state or that of dreamless sleep.

18. “As a large fish swims alternately to both banks of a river – the east and the west – so does the infinite being move to both these states: dreaming and waking.

19. “As a hawk or a falcon roaming in the sky becomes tired, folds its wings and makes for its nest, so does this infinite entity (purusha) hasten for this state, where, falling asleep, he cherishes no more desires and dreams no more dreams.

The Self…

…no objects present in the Self

So we can see in the above verses Yajnavalkya has described the three states and how the Self remains unaffected by the two states of waking or dreaming. Now Yajnavalkya proceeds to teach more about the Self. Using a series of metaphors he explains how no objects are present in the Self. Initially he compares it to the ecstacy of sexual orgasm in which one loses all knowledge of the body mind and world, one loses all sense of fear and misery, and one feels completely and totally fulfilled, not desiring anything more and with no trace of suffering:

21. “That indeed is his form-free from desires, free from evils, free from fear. As a man fully embraced by his beloved wife knows nothing that is without, nothing that is within, so does this infinite being (the self), when fully embraced by the Supreme Self, know nothing that is without, nothing that is within. That indeed is his form, in which all his desires are fulfilled, in which all desires become the self and which is free from desires and devoid of grief.”

Yajnavalkya then goes on to say that with realisation of the Self, everything is no longer what it appeared to be, and the Self is untouched by karma – good deeds and bad deeds – and also untouched by any suffering:

22. “In this state a father is no father, a mother is no mother, the worlds are no worlds, the gods are no gods, the Vedas are no the Vedas. In this state a thief is no thief, the killer of a noble brahmin is no killer, a chandala is no chandala, a paulkasa is no paulkasa, a monk is no monk, an ascetic is no ascetic. This form of his is untouched by good deeds and untouched by evil deeds, for he is then beyond all the woes of his heart.”

He then states that even in deep sleep the Self exists as pure consciousness, not conscious of any object, for there are no objects in deep sleep, but conscious somehow nonetheless, for its nature is imperishable eternal consciousness:

23. “And when it appears that in deep sleep it does not see, yet it is seeing though it does not see; for there is no cessation of the vision of the seer, because the seer is imperishable. There is then, however, no second thing separate from the seer that it could see.

The above verse is essentially repeated for all the senses and mind, but then culminates at verses 31 and 32. I have here included the full sanskrit and Shankara’s commentary for these important verses. The verses state that when objective phenomena appear, ie. in the dream or waking states, it appears as if we can see something separate from us or perceive something separate from us. This apparent perception is due to ignorance or illusion. However, when we return to deep sleep, that is the Self:

Verse 4.3.31:

यत्र वा अन्यदिव स्यात्, तत्रान्योऽन्यत्पश्येत्, अन्योऽन्यज्जिघ्रेत्, अन्योऽन्यद्रसयेत्, अन्योऽन्यद्वदेत्, अन्योऽन्यच्छृणुयात्, अन्योऽन्यन्मन्वीत, अन्योऽन्यत्स्पृशेत्, अन्योऽन्यद्विजानीयात् ॥ ३१ ॥

yatra vā anyadiva syāt, tatrānyo’nyatpaśyet, anyo’nyajjighret, anyo’nyadrasayet, anyo’nyadvadet, anyo’nyacchṛṇuyāt, anyo’nyanmanvīta, anyo’nyatspṛśet, anyo’nyadvijānīyāt || 31 “||

31. In the waking and dream states, when there is something else, as it were, then one can see something, one can smell some-thing, one can taste something, one can speak something, one can hear something, one can think something, one can touch something, or one can know something.

Shankara’s commentary on 4.3.31:

It has been said that in the state of profound sleep there is not, as in the waking and dream states, that second thing [ie. objects] differentiated from the self which it can know; hence it knows no particulars [ie. objects] in profound sleep. Here it is objected: If this is its nature, why does it give up that nature and have particular knowledge [of objects]? If, on the other hand, it is its nature to have this kind of knowledge, why does it not know particulars [ie. objects] in the state of profound sleep? The answer is this: When, in the waking or dream state, there is something else besides the self, as it were, presented by ignorance, then one, thinking of oneself as different from that something—although there is nothing different from the self, nor is there any self different from it—can see something. This has been shown by a referrence to one’s experience in the dream state in the passage, ‘As if he were being killed, or overpowered’(IV. iii. 20). Similarly one can smell, taste, speak, hear, think, touch and know something.

Verse 4.3.32:

सलिल एको द्रष्टाद्वैतो भवति, एष ब्रह्मलोकः सम्राडिति हैनमनुशशास याज्ञवल्क्यः, एषास्य परमा गतिः, एषास्य परमा संपत्, एषोऽस्य परमो लोकः, एषोऽस्य परम आनन्दः; एतस्यैवानन्दस्यान्यानि भूतानि मात्रामुपजीवन्ति ॥ ३२ ॥

salila eko draṣṭādvaito bhavati, eṣa brahmalokaḥ samrāḍiti hainamanuśaśāsa yājñavalkyaḥ, eṣāsya paramā gatiḥ, eṣāsya paramā saṃpat, eṣo’sya paramo lokaḥ, eṣo’sya parama ānandaḥ; etasyaivānandasyānyāni bhūtāni mātrāmupajīvanti || 32 ||

32. In the deep sleep state, it becomes (transparent) like water, one, the witness, and without a second. This is the world (state) of Brahman, O Emperor. Thus did Yājñavalkya instruct Janaka: This is its supreme attainment, this is its supreme glory, this is its highest world, this is its supreme bliss. On a particle of this very bliss other beings live.

Shankara’s commentary on 4.3.32:

When, however, that ignorance which presents things other than the self is at rest, in that state of profound sleep, there being nothing separated from the self by ignorance, what should one see, smell, or know, and through what? Therefore, being fully embraced by his own self-luminous Supreme Self, the Jīva becomes infinite, perfectly serene, with all his objects of desire attained, and the self the only object of his desire, transparent like water, one, because there is no second: It is ignorance which separates a second entity, and that is at rest in the state of profound sleep; hence ‘one.’ The witness, because the vision that is identical with the light of the self is never lost. And without a second, for there is no second entity different from the self to be seen. This is immortal and fearless. This is the world of Brahman, the world that is Brahman: In deep sleep the self, bereft of its limiting adjuncts, the body and organs, remains in its own supreme light of the Ātman [the Self], free from all relations, O Emperor. Thus did Yājñavalkya instruct Janaka. This is spoken by the Śruti.

How did he instruct him? This is its supreme attainment, the attainment of the individual self.

The other attainments, characterised by the taking of a body, from the state of Hiraṇyagarbha down to that of a clump of grass, are created by ignorance [Tom: ie. all objects of the universe are creations of Ignorance; we can see Shankara is equating ignorance with Maya here, as Maya is traditionally said to be the cause of the phenomenal universe] and therefore inferior to this, being within the sphere of ignorance. But this identification with all, in which one sees nothing else, hears nothing else, knows nothing olse, is the highest of all attainments such‘as identity with the gods, that are achieved through meditation and rites. This too is its supreme glory, the highest of all its splendours, being natural to it; other glories are artificial. Likewise this is its highest world; the other worlds, which are the result of its past work, are inferior to it; this, however, is not attainable by any action, being natural; hence ‘this is its highest world.’ Similarly this is its supreme bliss, in comparison with the bther joys that are due to the contact of the organs with their objects, since it is eternal; for another Śruti says, ‘That which is infinite is bliss’ (Ch. VII. xxiii. 1). ‘That in which one sees something. . . . knows something, is puny,’ mortal, secondary joy. But this is the opposite of that hence ‘this is its supreme bliss.’ On a particle of this very bliss, put forward by ignorance, and perceived only during the contact of the organs with their objects, other beings live. Who are they? Those that have been separated from that bliss by ignorance, and are considered different from Brahman. Being thus different, they subsist on a fraction of that bliss which is perceived through the contact of the organs with their objects.

Tom’s concluding remarks:

We can see that in the above two verses Shankara and Yajnavalkya are stating that:

–The Self cannot be attain by various karmas or works, for these are relating to objective phenomena only which occur only in the dream and waking states. ie. works or practices can only occur in the waking or dream states.

-However, the Self already is, it is already our True Actual Nature, naturally unattached and unaffected by it all, naturally beyond desire and suffering, its nature being happiness or bliss and oneness in which there is no sense of other.

– In deep sleep, when there are no adjuncts, ie. no objective phenomena such as body, world or mind, then there is only the Self. Shankara states ‘this is spoken by shruti’, shruti referring to the revealed scriptures that are the vedas and upanishads, meaning that this teaching comes from the highest authority.

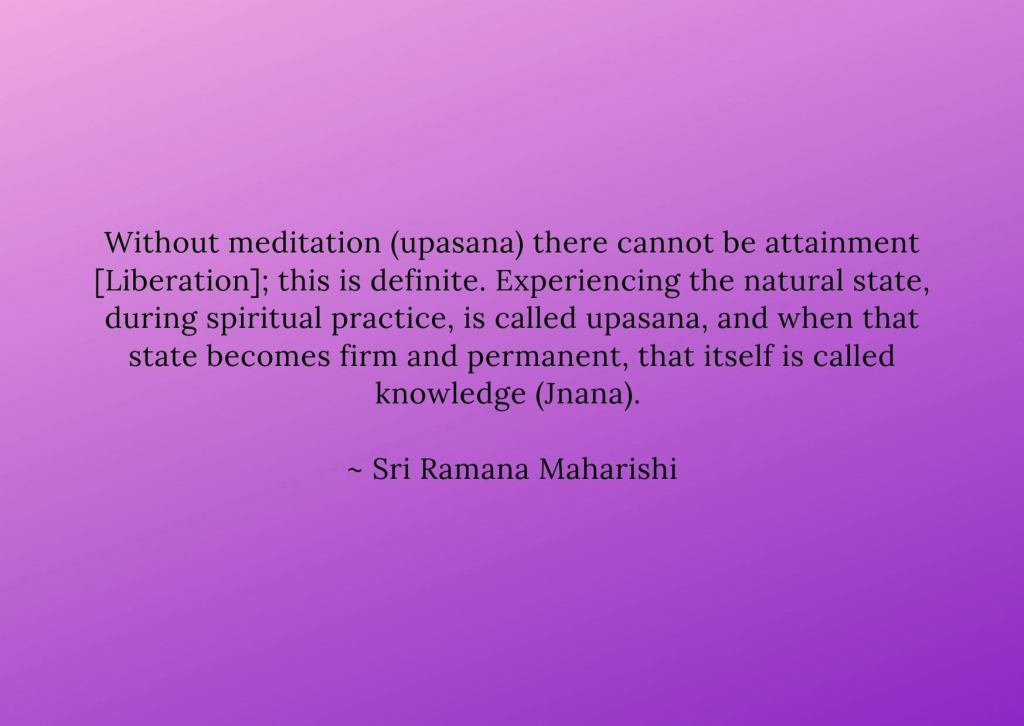

This same teaching is given by Sri Ramana Maharshi here. Note that it is only from the point of view of ignorance (in the waking state) that deep sleep is considered to be a third state (and not the Pure Self) and it is inferred (ignorantly in the waking state) that a seed of ignorance remains in this deep sleep state in order to account for the ‘fact’ that we are not liberated through sleep.

– All else, ie. all objective phenomena, are created and presented to us by ignorance (ie. ignorance and maya are one), and so we are separated from the Bliss of Brahman by our seeing of objects ‘outside of us’.

The Upanishad tells us Thus did Yājñavalkya instruct Janaka

Note that a clear and direct method for realisation is not given in this section of the Upanishad, although it is hinted at. For more on this see here which is where the instruction on the method on how to attain liberation is given in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad by our friend, Sage Yajnavalkya.

Note that this above section of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad also tallies with and is indirectly explained further by Sri Ramana Maharshi’s method of wakeful-sleep, a wonderful and simple explanation of the path to liberation.

Also see:

Deep Sleep and Self-Realisation