Here are some very potent nondual teachings that are well worth taking the time and making the effort to read. The teachings here tend not to be found in many other places. I have found that even many so-called teachers of Advaita Vedanta seem to teach something else, especially in the West, so it pays to read the traditional teachings for yourself and learn the true path to liberation directly from the source texts.

Advaita Bodha Deepika was one of Ramana Maharshi’s favourite scriptures and he often recommended it for seekers to read. It is one of the few traditional scriptures that comprises a structured and comprehensive explanation of the various methods of Advaita Vedanta. All chapters of this work are great, but this following chapter on ‘Sakshatkara’ or ‘Realisation’ has some key teachings that are often lost in some contemporaneous renditions of Advaita Vedanta and nondual teachings in general.

Without the vital understanding presented in this chapter, true liberation is unlikely to result. The opposite is also true – putting the words of this chapter into practice sets one off on the direct path to liberation.

This particular teaching starts at Chapter 7. Thus far in the text, the Self or Awareness has already been pointed out and described to the student, and the student, being open to the teachings, has gained a first-hand understanding of this. The student now feels that liberation has been gained, but then the teaching continues…the teacher points out the egotism-ignorance is still at play and then explains how to remove it…

Please let us make obeisance to the Lord-our-Self, and without further ado – enjoy;

The chapter starts with a recap of what has been discussed thus far in preceding chapters, and I have added bold type for emphasis of what I felt are some key points:

Advaita Bodha Deepika

Chapter 7 – Sakshatkara or Realisation

1. In the foregoing chapter it was said that direct knowledge must first be gained and then the latent tendencies of the mind wiped out so that Brahman may be realised. Now Realisation is dealt with. The master says: Wise son, now that you have gained direct knowledge by enquiry into the Self, you should proceed with meditation.

2. DISCIPLE: Master, now that I have gained direct knowledge by enquiry and my task is finished why should I meditate further and to what end?

3-4. MASTER: Though by reflection, direct knowledge of the Self has been gained, Brahman cannot be realised without meditation. In order to experience `I am Brahman’ you must practise meditation.

5-6.: D.: You ask me to pursue meditation for realising Brahman. I have already gained direct knowledge by enquiry into the sacred text. Why should I now practise meditation?

M.: If you mean to say that enquiry into the sacred text results in realising Brahman, who can deny it? No one. Truly this enquiry must end in the realisation of Brahman. Let us now enquire into the meaning of the text. Whose identity with whom is implied in it? It must be of the consciousness witnessing the five sheaths of the individual, the implied meaning of `thou’ with Brahman, the implied meaning of `That’; it cannot be of the Jiva, i.e., the personal soul with Brahman. By enquiry the identity of the witnessing consciousness with Brahman has certainly been found. Of what use can this identity of the witness with Brahman be to you?

7. D.: On enquiry into the meaning of the sacred text, when one has realised that the witness is Brahman and vice versa, how can you raise the question `Of what use can it be to the person?’ Its use is evident. Formerly the seeker was ignorant of the identity and now by enquiry he is aware of it.

M.: By enquiry you have certainly known that the witness is Brahman and that the unbroken, all-perfect Brahman is the witness. Still this knowledge is not the end and cannot serve your purpose. Suppose a poor beggar who was ignorant of the fact that a king residing in a fort was the emperor of the world, later knew it. How does this newly acquired knowledge improve his position? It cannot serve any useful purpose for him.

- D.: Before enquiry, ignorance prevails. After enquiry, knowledge is gained that the witness is Brahman. Now knowledge has taken the place of ignorance. This is the use.

M.: How does this affect the fact? Whether you have known it or not, the witness ever remains Brahman. Your knowledge of the fact has not made Brahman, the witness. Whether the poor beggar knew it or not, the king in the fort was the emperor. His knowledge did not make an emperor of the king in the fort. Now that you have known the witness to be Brahman, what has happened to you? Tell me. There can be no change in you.

- D.: Why not? There is a difference. The sacred text teaches `That thou art’. On enquiring into its significance I have found that the witness of the five sheaths in me is the same as Brahman. From this I have known that I am Brahman, which forms another sacred text. To me who was ignorant of the witness being the same as Brahman, this knowledge has dawned, with the result that I have realised Brahman.

M.: How can you claim to have realised Brahman? If by the text `I am Brahman’ you understand yourself to be Brahman, who is this `I’ but the Jiva, the individual soul or the ego? How can the ego be Brahman? Just as even with his knowledge of the king, the beggar cannot himself be the king, so also the changeful ego can never be identical with the changeless Brahman.

10-14. D.: Certainly so. But on enquiring `Who am I?’ it becomes plain that by non-enquiry the unchanging witness had mistaken the changing ego for himself. Now he knows `I am not the changing ego but remain its unchanging conscious witness’. Now it is but right that the witness should say, `I am Brahman’. What can be discordant in this?

M.: How can you hold that the witness says `I am Brahman?’ Does the unchanging witness or the changing ego say so? If you say that it is the witness, you are wrong. For the witness remains unchanging as the witness of the `false-I’. He is not the conceit itself. Otherwise he cannot have the quality of being the witness for he will himself be changing. Being unchanging the witness is free from the least trace of any notion such as `I’ or Brahman and cannot therefore know `I am Brahman’. There is no ground for your contention that the witness says so.

D.: Then who knows `I am Brahman’?

M.: From what has been said before, it must follow that the individual soul, the jiva, or the `false-I’ must have this knowledge.

D.: How does this follow?

M.: In order to be free from the repeated cycle of births and deaths, the ignorant man is obliged to practise the knowledge `I am Brahman’. There is no ignorance for the witness. When there is no ignorance, there can be no knowledge either. Only the ignorant must seek knowledge. Who but the `false-I’ can be the subject of ignorance or of knowledge? It is self-evident that the witnessing Self being the substratum on which knowledge or ignorance appears, must itself be free from them. On the contrary the `false-I’ is known to possess knowledge or ignorance. If you ask him `Do you know the Self witnessing you?’ And he will answer `Who is that witness? I do not know him’. Here the ignorance of the `false-I’ is obvious. On hearing the vedanta that there is an inner witness to him, indirectly he knows that the Self is his witness. Then enquiring into the Self, the veil of Ignorance that It does not shine forth, is drawn off and directly he knows the witnessing Self. Here again the knowledge of the `false-I’ is also clear. It is only the jiva and not the witness who has the knowledge or ignorance that there is, or is not, the inner witness. You must now admit that the jiva has the knowledge that `I am Brahman’. Now for the reason that the changing Jiva has become aware of the unchanging witness, he cannot be the same as the witness. Because he had seen him, the poor beggar cannot be the king. So also the changing Jiva cannot be the witness. Without being the witnessing Self, the changing entity cannot be Brahman. So this experience `I am Brahman’ is impossible.

- D.: How can you say that merely seeing the witness, I cannot know that I am the witness? Ignorant of his true being as the substratum or the witnessing consciousness, the Jiva moves about as the `false-I’. However on a careful enquiry into his true nature he knows the witness and identifies himself as the witness who is well-known to be the unbroken, all perfect Brahman. Thus the experience, `I am Brahman’, is real.

M.: What you say is true provided that the jiva can identify himself as the witness. The witness is undoubtedly Brahman. But how can the mere sight of the witness help the jiva merge himself into the witness? Unless the jiva remains the witness, he cannot know himself as the witness. Merely by seeing the king, a poor beggar cannot know himself to be the king. But when he becomes the king, he can know himself as the king. Similarly the jiva, remaining changeful and without becoming the unchanging witness, cannot know himself as the witness. If he cannot be the witness, how can he be the unbroken, all-perfect Brahman? He cannot be. Just as at the sight of the king in a fort, a poor beggar cannot become king and much less sovereign of the universe, so also only at the sight of the witness who is much finer than ether and free from traffic with triads, such as the knower, knowledge and the known, eternal, pure, aware, free, real, supreme and blissful, the jiva cannot become the witness, much less the unbroken, all-perfect Brahman, and cannot know `I am Brahman’.

- D.: If so, how is it that the two words of the same case ending (samanadhikarana) — `I’ and `Brahman’ — are placed in apposition in the sacred text `I am Brahman’? According to grammatical rules the sruti clearly proclaims the same rank to the jiva and Brahman. How is this to be explained?

17-18. M.: The common agreement between two words in apposition is of two kinds: mukhya and badha i.e., unconditional and conditional. Here the sruti does not convey the unconditional meaning.

D.: What is this unconditional meaning?

M.: The ether in a jar has the same characteristics as that in another jar, or in a room, or in the open. Therefore the one ether is the same as the other. Similarly with air, fire, water, earth, sunlight etc. Again the god in one image is the same as that in another and the witnessing consciousness in one being is the same as that in another. The sruti does not mean this kind of identity between the jiva and Brahman, but means the other, the conditional meaning.

D.: What is it?

M.: Discarding all appearances, the sameness of the substratum in all.

D.: Please explain this.

M.: `I am Brahman’ means that, after discarding the `false-I’, only the residual being or the pure consciousness that is left over can be Brahman — It is absurd to say that, without discarding but retaining the individuality, the jiva, on seeing Brahman but not becoming Brahman, can know himself as Brahman. A poor beggar must first cease to be beggar and rule over a state in order to know himself as king; a man desirous of god-hood first drowns himself in the Ganges and leaving this body, becomes himself a celestial being; by his extraordinary one-pointed devotion a devotee leaves off his body and merges into god, before he can know himself to be god. In all these cases when the beggar knows himself to be king, or the man to be celestial being, or the devotee to be god, they cannot retain their former individualities and also identify themselves as the superior beings. In the same way, the seeker of Liberation must first cease to be an individual before he can rightly say `I am Brahman’. This is the significance of the sacred text. Without completely losing one’s individuality one cannot be Brahman. Therefore to realise Brahman, the loss of the individuality is a sine qua non.

D.: The changeful individual soul cannot be Brahman. Even though he rids himself of the individuality, how can he become Brahman?

- M.: Just as a maggot losing its nature, becomes a wasp.A maggot is brought by a wasp and kept in its hive. From time to time the wasp visits the hive and stings the maggot so that it always remains in dread of its tormentor. The constant thought of the wasp transforms the maggot into a wasp. Similarly, constantly meditating on Brahman, the seeker loses his original nature and becomes himself Brahman. This is the realisation of Brahman.

- D.: This cannot illustrate the point, for the jiva is changing and falsely presented on the pure Being, Brahman, which is the Reality. When a false thing has lost its falsity, the whole entity is gone; how can it become the Reality?

- M.: Your doubt, how a superimposed falsity turns out to be its substratum, the Reality, is easily cleared. See how the nacre-silverceases to be silver and remains as nacre, or a rope-snake ceasing to be snake remains ever as rope. Similarly, with the jiva superimposed on the Reality, Brahman.

D.: These are illusions which are not conditioned (nirupadhika bhrama) whereas the appearance of the jiva is conditioned (sopadhika bhrama) and appears as a superimposition only on the internal faculty, the mind. So long as there is the mind, there will also be the jiva or the individual, and the mind is the result of past karma. As long as this remains unexhausted, the jiva must also be present. Just as the reflection of one’s face is contingent upon the mirror or water in front, so is individuality, on the mind, the effect of one’s past karma. How can this individuality be done away with?

M.: Undoubtedly individuality lasts as long as the mind exists. Just as the reflected image disappears with the removal of the mirror in front, so also individuality can be effaced by stilling the mind by meditation.

[Tom: this ‘stilling of mind’ means the stilling or removal of all thoughts, and is also known as Nirvikalpa Samadhi]

D.: The individuality being thus lost, the jiva becomes void. Having become void, how can he become Brahman?

M.: The jiva is only a false appearance not apart from its substratum. It is conditional on ignorance, or the mind, on whose removal the jiva is left as the substratum as in the case of a dream person.

22-23. D.: How?

M.: The waking man functions as the dreamer (taijasa) in his dreams. The dreamer is neither identical with nor separate from the waking man (visva). For the man sleeping happy on his bed has not moved out whereas as the dreamer he had wandered about in other places, busy with many things. The wanderer of the dream cannot be the man resting in his bed. Can he then be different? Not so either. For on waking from sleep, he says `In my dream I went to so many places, did so many things and was happy or otherwise’. Clearly he identifies himself with the experiencer of the dream. Moreover no other experiencer can be seen.

D.: Not different from nor identical with the waking experiencer, who is this dream-experiencer?

M.: Being a creation of the illusory power of sleep the dream experiencer is only an illusion like the snake on a rope. With the finish of the illusory power of dream, the dreamer vanishes only to wake up as the real substratum, the original individual self of the waking state. Similarly the empirical self, the jiva is neither the unchanging Brahman nor other than It. In the internal faculty, the mind, fancied by ignorance, the Self is reflected and the reflection presents itself as the empirical, changing and individual self. This is a superimposed false appearance. Since the superimposition cannot remain apart from its substratum, this empirical self cannot be other than the absolute Self.

D.: Who is this?

M.: Successively appearing in the ignorance-created mind and disappearing in deep sleep, swoon etc., this empirical self is inferred to be only a phantom. Simultaneously with the disappearance of the medium or the limiting adjunct (upadhi), the mind, the jiva becomes the substratum, the True Being or Brahman. Destroying the mind, the jiva can know himself as Brahman.

- D.: With the destruction of the limiting adjunct, the jiva being lost, how can he say `I am Brahman’?

M.: When the limiting ignorance of dream vanishes, the dreamer is not lost, but emerges as the waking experiencer. So also when the mind is lost, the jiva emerges as his true Being — Brahman. Therefore as soon as the mind is annihilated leaving no trace behind, the jiva will surely realise `I am the Being-Knowledge-Bliss, non-dual Brahman; Brahman is I, the Self ‘.

D.: In that case the state must be without any mode like that of deep sleep. How can there be the experience `I am Brahman’?

M.: Just as at the end of a dream, the dreamer rising up as the waking experiencer says `All along I was dreaming that I wandered in strange places, etc., but I am only lying down on the bed,’ or a madman cured of his madness remains pleased with himself, or a patient cured of his illness wonders at his past sufferings, or a poor man on becoming a king, forgets or laughs at his past penurious state, or a man on becoming a celestial being enjoys the new bliss, or a devotee on uniting with the Lord of his devotion remains blissful, so also the jiva on emerging as Brahman wonders how all along being only Brahman he was moving about as a helpless being imagining a world, god and individuals, asks himself what became of all those fancies and how he now remaining all alone as Being-Knowledge-Bliss free from any differentiation, internal or external, certainly experiences the Supreme Bliss of Brahman. Thus realisation is possible for the jiva only on the complete destruction of the mind and not otherwise.

- D.: Experience can be of the mind only. When it is destroyed,who can have the experience `I am Brahman’?

M.: You are right. The destruction of the mind is of two kinds: (rupa and arupa) i.e., in its form-aspect and in its formless aspect. All this while I have been speaking of destroying the former mind. Only when it ceases to be in its formless aspect, experience will be impossible, as you say.

D.: Please explain those two forms of the mind and their destruction.

M.: The latent impressions (vasanas) manifesting as modes (vrittis) constitute the form-aspect of the mind. Their effacement is the destruction of this aspect of mind. On the other hand, on the latencies perishing, the supervening state of samadhi in which there is no stupor of sleep, no vision of the world, but only the Being-Knowledge-Bliss is the formless aspect of mind. The loss of this amounts to the loss of the formless aspect of mind. Should this also be lost, there can be no experience — not even of the realisation of Supreme Bliss.

D.: When does this destruction take place?

M.: In the disembodiment of the liberated being. It cannot happen so long as he is alive in the body. The mind is lost in its form-aspect but not in its formless one of Brahman. Hence the experience of Bliss for the sage, liberated while alive.

26-27. D.: In brief what is Realisation?

M.: To destroy the mind in its form-aspect functioning as the limiting adjunct to the individual, to recover the pure mind in its formless aspect whose nature is only Being-Knowledge-Bliss and to experience `I am Brahman’ is Realisation.

D.: Is this view supported by others as well?

M.: Yes. Sri Sankaracharya has said: `Just as in the ignorant state, unmindful of the identity of the Self with Brahman, one truly believes oneself to be the body, so also after knowing to be free from the illusion of the body being the Self, and becoming unaware of the body, undoubtingly and unmistakably always to experience the Self as the Being-Knowledge-Bliss identical with Brahman is called Realisation’. `To be fixed as the Real Self is Realisation’, say the sages.

- D.: Who says it and where?

- M.: Vasishta has said in Yoga Vasishta: ‘Just as the mind in a stone remains quiet and without any mode, so also like the interior of the stone to remain without any mode and thought free, but not in slumber nor aware of duality, is to be fixed as the Real Self’.

[Tom: again, this ‘the mind…remains quiet and without any mode…not in slumber [sleep] nor aware of any duality’ clearly refers to nirvikalpa samadhi, also known as the state of wakeful sleep (jagrat sushupti)]

30-31. Therefore without effacing the form-aspect of the mind and remaining fixed as the true Self, how can anyone realise `I am Brahman’? It cannot be. Briefly put, one should still the mind to destroy one’s individuality and thus remain fixed as the Real Self of Being-Knowledge-Bliss, so that in accordance with the text `I am Brahman’ one can realise Brahman. On the other hand, on the strength of the direct knowledge of Brahman to say `I am Brahman’ is as silly as a poor beggar on seeing the king declaring himself to be the king. Not to claim by words but to be fixed as the Real Self and know `I am Brahman’ is Realisation of Brahman.

- D.: How will the sage be, who has undoubtingly, unmistakably and steadily realised Brahman?

M.: Always remaining as the Being-Knowledge-Bliss, nondual, all perfect, all-alone, unitary Brahman, he will be unshaken even while experiencing the results of the past karma now in fruition. (prarabdha).

33-35. D.: Being only Brahman, how can he be subject to the experiences and activities resulting from past karma?

M.: For the sage undoubtingly and unmistakably fixed as the real Self, there can remain no past karma. In its absence there can be no fruition, consequently no experience nor any activity. Being only without mode Brahman, there can be no experiencer, no experiences and no objects of experience. Therefore no past karma can be said to remain for him.

D.: Why should we not say that his past karma is now working itself out?

M.: Who is the questioner? He must be a deluded being and not a sage.

D.: Why?

M.: Experience implies delusion; without the one, the other cannot be. Unless there is an object, no experience is possible. All objective knowledge is delusion. There is no duality in Brahman. Certainly all names and forms are by ignorance superimposed on Brahman. Therefore the experiencer must be ignorant only and not a sage. Having already enquired into the nature of things and known them to be illusory names and forms born of ignorance, the sage remains fixed as Brahman and knows all to be only Brahman. Who is to enjoy what? No one and nothing. Therefore there is no past karma left nor present enjoyments nor any activity for the wise one.

36-37. D.: However we do not see him free from the experience of past karma; on the other hand he goes through them like an ordinary ignorant man. How is this to be explained?

M.: In his view there is nothing like past karma, enjoyments or activities.

D.: What is his view?

M.: For him there is nothing but the pure, untainted Ether of Absolute Knowledge.

D.: But how is he seen to pass through experiences?

M.: Only the others see him so. He is not aware of it.

38-39. D.: Is this view confirmed by other authorities?

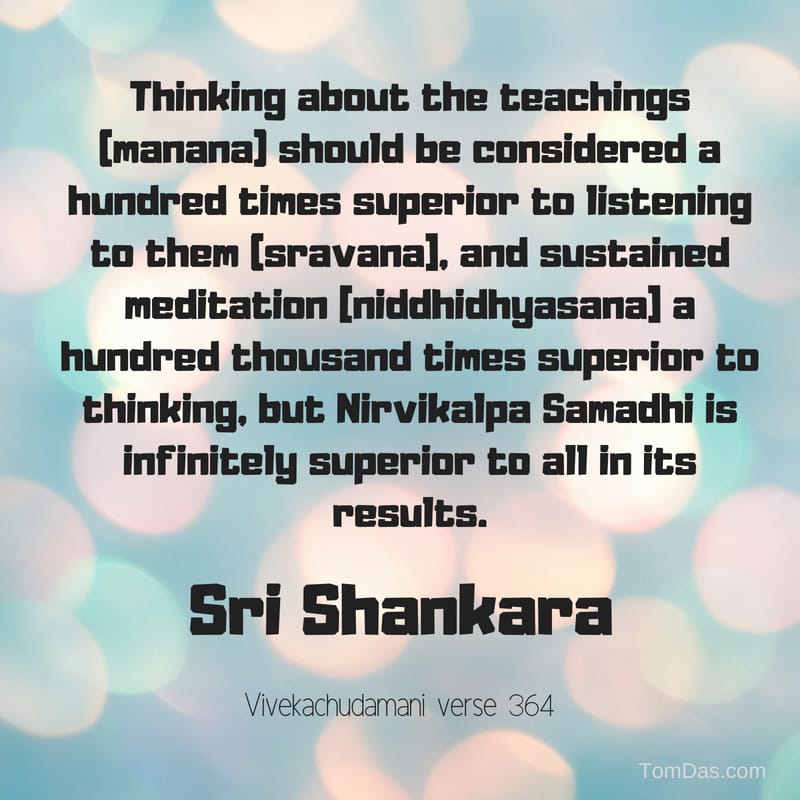

M.: In Vivekachudamani, Sri Acharya [Shankara] has said `Simultaneous with the dawn of knowledge, ignorance with all its effects flees away from the sage and so he cannot be an enjoyer. However, the ignorant wonder how the sage continues to live in the body and act like others. From the ignorant point of view, the scriptures have admitted the momentum of past karma, but not from the point of view of the sage himself ‘.

- D.: If truly he is no enjoyer, why should he appear to others to be so?

M.: Owing to their ignorance, the others regard him as an enjoyer.

41-43. D.: Can this be so?

M.: Yes. To the ignorant only the non-dual, pure Ether of Absolute Knowledge manifests Itself as various beings, the world, God, different names and forms, I, you, he, it, this and that. Like the illusion of a man on a post, silver on nacre, snake on rope, utensils in clay, or ornaments in gold, different names and forms on the Ether of Knowledge delude the ignorant. The sage who, by practice of knowledge, has destroyed ignorance and gained true knowledge, will always remain only as the Ether of Absolute Knowledge, unaware of enjoyments of fruits of actions or of worldly activities. Being That, he can be aware as the Ether of Knowledge only. Nevertheless, owing to their ignorance others see him otherwise, i.e., as an embodied being acting like themselves. But he remains only pure, untainted ether, without any activity.

44-46. D.: Can it be illustrated how the sage remaining himself inactive, appears active to others?

M.: Two friends sleep side by side. One of them reposes in dreamless sleep whereas the other dreams that he is wandering about with his friend. Though in complete repose, this man appears active to the dreamer. Similarly although the sage remains inactive as the blissful Ether of Absolute Knowledge, he appears to be active to those who in ignorance remain always caught up in names and forms.

It must now be clear that the realised sage being the pure Self is not involved in action but only appears to be so.

47-48. D.: Not that there are no experiences whatever for the realised sage, but they are only illusory. For Knowledge can destroy the karma already stored and the future karma (sanchita and agamya) but not the karma which having already begun to bear fruit (prarabdha) must exhaust itself. As long as it is there, even from his own point of view, activities will persist, though illusory.

M.: This cannot be. In which state do these three kinds of karma exist — knowledge or ignorance? Owing to delusion; it must be said `they are operative only in ignorance.’ But in knowledge there being no delusion, there is no prarabdha. Always remaining undeluded as the transcendental Self, how can the delusion of the fruition of karma occur to one? Can the delusion of dream-experience return to him who has awakened from it? To the disillusioned sage there can be no experience of karma. Always he remains unaware of the world but aware of the Self as the non-dual, unbroken, unitary, solid, without any mode Ether of Absolute Knowledge, and of nothing besides.

- D.: The Upanishad admits past karma in the Text `As long as his past karma is not exhausted the sage cannot be disembodied, and there will be illusory activities for him’.

M.: You are not right. The activities and experiences of the fruits of action and the world seem illusory to the practiser of Knowledge and they completely vanish to the accomplished sage. The practiser practises as follows: `I am the witness; the objects and activities are seen by and known to me. I remain conscious and these are insentient. Only Brahman is real; all else is unreal.’ The practice ends with the realisation that all these are insentient consisting of names and forms and cannot exist in the past, present or future, therefore they vanish. There being nothing to witness, witnessing ends by merging into Brahman. Only the Self is now left over as Brahman. For the sage aware of the Self only, there can remain only Brahman and no thought of karma, or worldly activities.

D.: Why then does the sruti mention past karma in this connection?

M.: It does not refer to the accomplished sage.

D.: Whom does it refer to?

M.: Only to the ignorant.

D.: Why?

M.: Although from his own point of view, the sage has no enjoyment of the fruits of actions, yet the ignorant are deluded on seeing his activities. Even if told there is no enjoyment for him, the ignorant will not accept it but continue to doubt how the sage remains active. To remove such doubt, the sruti says to the ignorant that prarabdha still remains for the sage. But it does not say to the sage `You have prarabdha’. Therefore the sruti which speaks of residual prarabdha, for the sage, really does not speak of it from his point of view.

50-51. D.: Realisation can result only after complete annihilation of individuality. But who will agree to sacrifice his individuality?

M.: Being eager to cross over the ocean of the misery of repeated births and deaths and realise the pure, eternal Brahman, one will readily sacrifice one’s individuality. Just as the man desirous of becoming a celestial being, willingly consigns himself to the fire or the Ganges in order to end this human life and emerge as a god, so also the seeker of Liberation will by practice of sravana, manana, and nidhidhyasana, (i.e., hearing, reflection and meditation) sacrifice his individuality to become the Supreme Brahman.

- Here ends the Chapter on Realisation. Diligently studying and understanding this, the seeker will kill the mind which is the limiting adjunct that causes individuality to manifest and ever live as Brahman only.

See here for how the teachings in this chapter lead to Silence or the Ultimate Means to Liberation

Also see here for Shankara’s writing on this: Shankara on the Mind, Samadhi, Manonasa (destruction of mind), and Liberation